Difference between revisions of "Social cost-benefit analysis"

| (52 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Social]][[Category:Economic]] |

|||

= Social cost-benefit analysis = |

|||

'''Social cost-benefit analysis''' is a systematic and cohesive method to survey all the impacts caused by an urban development project<ref name="ftn84"> In the Netherlands, conducting a social cost- |

[[File:ae.png|25px|right|This is a page providing background in a specific field of expertise]]'''Social cost-benefit analysis''' is a systematic and cohesive [[Economic tools|economic tool]](method) to survey all the impacts caused by an urban development project<ref name="ftn84"> In the Netherlands, conducting a social cost-benefit analysis is mandatory for major infrastructure projects.</ref>. It comprises not just the financial effects (investment costs, direct benefits like tax and fees, et cetera), but all the social effects, like: pollution, safety, indirect (labour) market, legal aspects, et cetera. The main aim of a social cost-benefit analysis is to attach a price to as many effects as possible in order to uniformly weigh the above-mentioned heterogeneous effects. As a result, these prices reflect the value a society attaches to the caused effects, enabling the decision maker to form a statement about the net social welfare effects of a project. |

||

== Relevance == |

|||

An advantage of an social cost-benefit analysis is that it enables investors to systematically and cohesively compare different project alternatives. In that case, these alternatives will not just be compared intrinsically, but will also be set against the null alternative hypothesis. |

|||

Knowledge about [[Economic tools|economic models/tools]] such as the social cost-benefit analysis can help the urban planner to systematically survey all the relevant (socio-economic) impact caused by an urban development and security threats. This insight will help the responsible urban planners to make the best choices from an socio-economic point of view. |

|||

== The null hypothesis == |

== The null hypothesis == |

||

A major advantage of a social cost-benefit analysis is that it enables investors to systematically and cohesively compare different project alternatives. Hence, these alternatives will not just be compared intrinsically, but will also be set against the "null alternative hypothesis". This hypothesis describes "the most likely" scenario development in case a project will not be executed. Put differently, investments on a smaller scale will be included in the null alternative hypothesis in order to make a realistic comparison in a situation without "huge" investments. |

|||

== Measured impacts == |

== Measured impacts == |

||

The social cost-benefit analysis calculates the direct ([[Primary economic impact|primary]]), indirect ([[Secondary economic impact|secondary]]) and external effects: |

The social cost-benefit analysis calculates the direct ([[Primary economic impact|primary]]), indirect ([[Secondary economic impact|secondary]]) and external effects: [[File:Playtime construction.JPG|thumb|Construction site]] |

||

* Direct effects are the costs and benefits that can be directly linked to the owners/users of the project properties (e.g., the users and the owner of a building or highway). |

* Direct effects are the costs and benefits that can be directly linked to the owners/users of the project properties (e.g., the users and the owner of a building or highway). |

||

* Indirect effects are the costs |

* Indirect effects are the costs and benefits that are passed on to the producers and consumers outside the market with which the project is involved (e.g., the owner of a bakery nearby the new building, or a business company located near the newly planned highway). |

||

* [[External effects]] are the costs and benefits that cannot be passed on to any existing |

* [[External effects]] are the costs and benefits that cannot be passed on to any existing market because they relate to issues like the environment (noise, emission of CO2 etc.), safety (traffic, external security) and nature (biodiversity, dehydration etc.). |

||

| ⚫ | The model engineers try to quantify and |

||

| ⚫ | The model engineers try to quantify and monetise as much effects as possible. Effects that cannot be monetised are presented in such a way that they can be compared. This way, policy-makers can include these effects in their final judgement if an urban planning project (or a particular variation) is worth investing in. The method of monetising effects can also influence the outcome of a social cost-benefit analysis and predictions will always remain uncertain. Therefore, the results of a social cost-benefit analysis are not absolute. Nevertheless, it is a sufficient instrument to investigate the strong and weak points of the different alternatives. |

||

== Results of a social cost-benefit analysis == |

== Results of a social cost-benefit analysis == |

||

The result of a social cost-benefit analysis are: |

The result of a social cost-benefit analysis are: |

||

| Line 26: | Line 27: | ||

# ''Presentation of the uncertainties and risks''. A social cost-benefit analysis has several methods to take economic risks and uncertainties into account. The policy decision should be based on calculated risk. |

# ''Presentation of the uncertainties and risks''. A social cost-benefit analysis has several methods to take economic risks and uncertainties into account. The policy decision should be based on calculated risk. |

||

== |

==Value of a statistical life (VASL)== |

||

A cost-benefit analysis can help to determine if a certain security measure designed to reduce the risk of death is worthwhile from an economic perspective. In order to do this, one needs to determine the costs of the specific measure, how many lives statistically (or in probability terms) are affected, and, finally, the (monetary) value of preventing a lethal fatality (the Value of a Statistical Life). The cost of preventing a lethal fatality can subsequently be compared with societal value of a statistical life (see example below). |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Note that VASL is no the value being placed on a life. It is just another way of expressing what a society is prepared to pay to mitigate a certain risk, and should not be confused with the value society might put on the life of a real person, for example in court<ref> For more information on this subject, see e.g.:Ashenfelter, O. (2006): Measuring the Value of a Statistical Life: Problems and Prospects. NBER Working Paper Series. No. 11916. Online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w11916.pdf?new_window=1.</ref>. |

|||

== Moral (ethical) aspects of a social economic analysis == |

|||

Moral (or ethical) issues are the foundation of any social-economic decision. At this point we mention three aspects of this foundation: |

|||

Case example: dedicated surveillance on location |

|||

{{quote|A paper by Stewart and Mueller (2008)<ref>Stewart, M.G., J. Mueller (2008): A risk and cost-benefit assessment of United States aviation security measures. Springer Science.</ref> performed a cost-benefit analysis of two aviation security measures, one of them the Federal Air Marshal Service. They conclude that even if the Air Marshal surveillance prevents one 9/11 replication each decade, the $900 million annual spending on Air Marshal Service fails a cost-benefit analysis at an annual estimated cost of $180 million per life saved (compared to a societal willingness to pay to save a life of $1 - $10 million per saved life).}} |

|||

=== The individual versus the well being of the majority === |

|||

The aim of a social cost-benefit analysis is to select the project with the highest social cost-benefit ratio that will lead to a maximization of wealth in a society. But what if the planned expansion of a new airport will indeed increase the (economic) well being of a region, but will reduce the quality of life for people living close to the airport significantly? Put differently, is the wellbeing of the mass always more valuable than that of the individual elements it exists of? |

|||

== Risk of double counting == |

|||

| ⚫ | The impact of an urban development project can be measured in two or more ways. For example, when an improved highway reduces travel time, the value of real estate property in areas served by the highway will be enhanced. The increase in property values due to the project is a possible way to measure the benefits of a project. But if the increased property values are included, it is unnecessary to include the value of the time saved by the improvement in the highway. Unnecessary, because the value of the real estate property went up because of improvement in reach ability, so including both the increase in property values and the time saving reduction, would lead to a double counting. |

||

=== The economic value of a human life and the environment === |

|||

Another source of controversy is placing a monetary value of human life, for example, when assessing safety measures against terrorism. It is kind of cold-blooded to make a cost-benefit analysis of the economic side of human loss. But, without placing a financial value on life itself, a social cost-benefit analysis would lose its value, especially when the purpose of a project is to improve the safety of local residents. The same kind of moral issues can be raised when the environment is valued as a provider of services to humans, sucha s safe water supply and pollination. Also here, one can wonder if it is always possible to value the environment, especially because one cannot afford to make mistakes. |

|||

==Limits of economic methods == |

|||

Like any other economic tool, social cost-benefit analysis has its [[Limits of economic analysis|fundamental and methodological limits]]. In addition, [[Moral aspects of socio economic methods|moral aspects of socio-economic methods]] are a fundamental aspect of any economic decision. The public interest is more than the difference between financial costs and benefits, and includes ethical aspects like balance between individual and collective interests, the intrinsic value of nature and human life, the (universal) right to live in a secure environment, and so on. |

|||

=== Who deserves safety? === |

|||

A third source of moral controversy comes from the question if everyone deserves protection from (terrorist) threats or only the wealthy? This is a question policy makers and urban planners have to deal with every day. |

|||

== Related subjects == |

|||

Urban planning processes employ a host of other economic tools/models: |

|||

* [[Input-output analysis|Input-output analysis]] |

|||

* [[Economic Impact Study|Economic impact study]] |

|||

* [[Business case|Business case]] |

|||

* [[Other economic tools|Other economic tools]] |

|||

* [[Economic tools|Economic tools]] |

|||

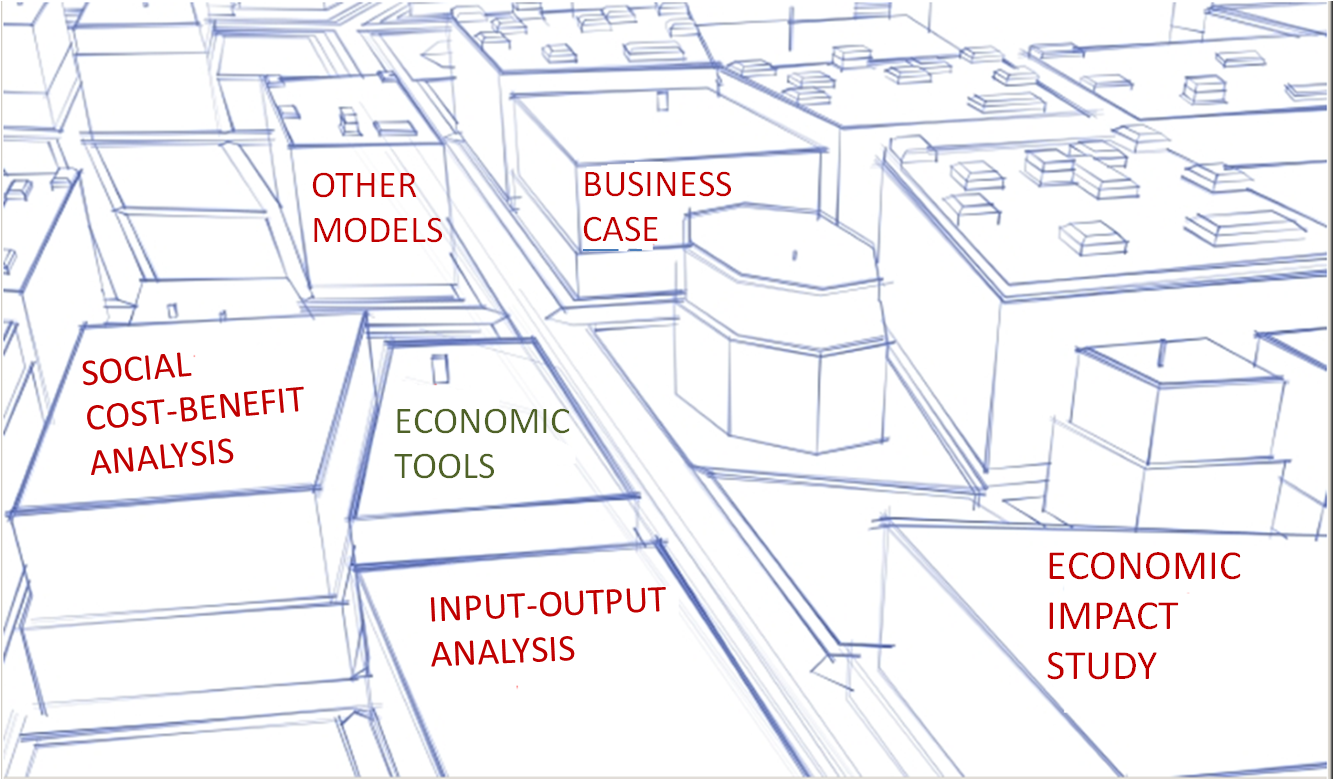

See also the clickable map below: |

|||

<imagemap> |

|||

Image:Economic_tools_v7.png| 350 px |

|||

rect 60 321 319 487 [[Social cost-benefit analysis|Social cost-benefit analysis]] |

|||

rect 360 550 716 763 [[Input-output analysis|Input-output analysis]] |

|||

rect 382 349 600 500 [[Economic tools|Economic tools]] |

|||

rect 289 148 456 277 [[Other economic tools|Other economic tools]] |

|||

rect 574 162 790 271 [[Business case|Business case]] |

|||

rect 978 521 1301 759 [[Economic Impact Study|Economic impact study]] |

|||

desc bottom-left |

|||

== References == |

|||

</imagemap> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Other related subjects: |

|||

= MAP = |

|||

* [[Economic tools]] |

|||

<websiteFrame> |

|||

* [[Economic impact]] |

|||

website=http://securipedia.eu/cool/index.php?wiki=securipedia.eu&concept=Social_cost-benefit_analysis |

|||

* [[Economic dimension of urban planning]] |

|||

height=1023 |

|||

width=100% |

|||

border=0 |

|||

scroll=auto |

|||

align=middle |

|||

</websiteFrame> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

<headertabs/> |

|||

Latest revision as of 23:05, 19 January 2018

Social cost-benefit analysis is a systematic and cohesive economic tool(method) to survey all the impacts caused by an urban development project[1]. It comprises not just the financial effects (investment costs, direct benefits like tax and fees, et cetera), but all the social effects, like: pollution, safety, indirect (labour) market, legal aspects, et cetera. The main aim of a social cost-benefit analysis is to attach a price to as many effects as possible in order to uniformly weigh the above-mentioned heterogeneous effects. As a result, these prices reflect the value a society attaches to the caused effects, enabling the decision maker to form a statement about the net social welfare effects of a project.

Contents

Relevance

Knowledge about economic models/tools such as the social cost-benefit analysis can help the urban planner to systematically survey all the relevant (socio-economic) impact caused by an urban development and security threats. This insight will help the responsible urban planners to make the best choices from an socio-economic point of view.

The null hypothesis

A major advantage of a social cost-benefit analysis is that it enables investors to systematically and cohesively compare different project alternatives. Hence, these alternatives will not just be compared intrinsically, but will also be set against the "null alternative hypothesis". This hypothesis describes "the most likely" scenario development in case a project will not be executed. Put differently, investments on a smaller scale will be included in the null alternative hypothesis in order to make a realistic comparison in a situation without "huge" investments.

Measured impacts

The social cost-benefit analysis calculates the direct (primary), indirect (secondary) and external effects:

- Direct effects are the costs and benefits that can be directly linked to the owners/users of the project properties (e.g., the users and the owner of a building or highway).

- Indirect effects are the costs and benefits that are passed on to the producers and consumers outside the market with which the project is involved (e.g., the owner of a bakery nearby the new building, or a business company located near the newly planned highway).

- External effects are the costs and benefits that cannot be passed on to any existing market because they relate to issues like the environment (noise, emission of CO2 etc.), safety (traffic, external security) and nature (biodiversity, dehydration etc.).

The model engineers try to quantify and monetise as much effects as possible. Effects that cannot be monetised are presented in such a way that they can be compared. This way, policy-makers can include these effects in their final judgement if an urban planning project (or a particular variation) is worth investing in. The method of monetising effects can also influence the outcome of a social cost-benefit analysis and predictions will always remain uncertain. Therefore, the results of a social cost-benefit analysis are not absolute. Nevertheless, it is a sufficient instrument to investigate the strong and weak points of the different alternatives.

Results of a social cost-benefit analysis

The result of a social cost-benefit analysis are:

- An integrated way of comparing the different effects. All relevant costs and benefits of the different project implementations (alternatives) are identified and monetized as far as possible. Effects that cannot be monetized are described and quantified as much as possible.

- Attention for the distribution of costs and benefits. The benefits of a project do not always get to the groups bearing the costs. A social cost-benefit analysis gives insight in who bears the costs and who derives the benefits.

- Comparison of the project alternatives. A social cost-benefit analysis is a good method to show the differences between project alternatives and provides information to make a well informed decision.

- Presentation of the uncertainties and risks. A social cost-benefit analysis has several methods to take economic risks and uncertainties into account. The policy decision should be based on calculated risk.

Value of a statistical life (VASL)

A cost-benefit analysis can help to determine if a certain security measure designed to reduce the risk of death is worthwhile from an economic perspective. In order to do this, one needs to determine the costs of the specific measure, how many lives statistically (or in probability terms) are affected, and, finally, the (monetary) value of preventing a lethal fatality (the Value of a Statistical Life). The cost of preventing a lethal fatality can subsequently be compared with societal value of a statistical life (see example below).

Note that VASL is no the value being placed on a life. It is just another way of expressing what a society is prepared to pay to mitigate a certain risk, and should not be confused with the value society might put on the life of a real person, for example in court[2].

Case example: dedicated surveillance on location

A paper by Stewart and Mueller (2008)[3] performed a cost-benefit analysis of two aviation security measures, one of them the Federal Air Marshal Service. They conclude that even if the Air Marshal surveillance prevents one 9/11 replication each decade, the $900 million annual spending on Air Marshal Service fails a cost-benefit analysis at an annual estimated cost of $180 million per life saved (compared to a societal willingness to pay to save a life of $1 - $10 million per saved life).

Risk of double counting

The impact of an urban development project can be measured in two or more ways. For example, when an improved highway reduces travel time, the value of real estate property in areas served by the highway will be enhanced. The increase in property values due to the project is a possible way to measure the benefits of a project. But if the increased property values are included, it is unnecessary to include the value of the time saved by the improvement in the highway. Unnecessary, because the value of the real estate property went up because of improvement in reach ability, so including both the increase in property values and the time saving reduction, would lead to a double counting.

Limits of economic methods

Like any other economic tool, social cost-benefit analysis has its fundamental and methodological limits. In addition, moral aspects of socio-economic methods are a fundamental aspect of any economic decision. The public interest is more than the difference between financial costs and benefits, and includes ethical aspects like balance between individual and collective interests, the intrinsic value of nature and human life, the (universal) right to live in a secure environment, and so on.

Related subjects

Urban planning processes employ a host of other economic tools/models:

See also the clickable map below:

Other related subjects:

Footnotes and references

- ↑ In the Netherlands, conducting a social cost-benefit analysis is mandatory for major infrastructure projects.

- ↑ For more information on this subject, see e.g.:Ashenfelter, O. (2006): Measuring the Value of a Statistical Life: Problems and Prospects. NBER Working Paper Series. No. 11916. Online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w11916.pdf?new_window=1.

- ↑ Stewart, M.G., J. Mueller (2008): A risk and cost-benefit assessment of United States aviation security measures. Springer Science.