Security threat: actors

A criminal, a term that has not been used in literature within the past decade, also known as a perpetrator, is an individual that conducts criminal behavior and thus deviating him or herself from society. Members of a society often see criminals as “the other”. They do not see themselves as part of the same group. Durkheim described the phenomenon of ‘moral superiority’ as a feeling of moral outrage towards the criminal ‘other’. These feelings functions as a positive social function, improving a sense of community among members of society.[1]

Crime can be conducted in groups or by individuals. Crimes that are committed by individuals often have different motivations and modus operandi than crimes that are committed by groups or members of a group. Individual crimes often have an emotional, compulsive or mental illness component or a mixture of components, whereas crimes committed by groups are often solely financially or ideologically motivated.

Contents

Individuals

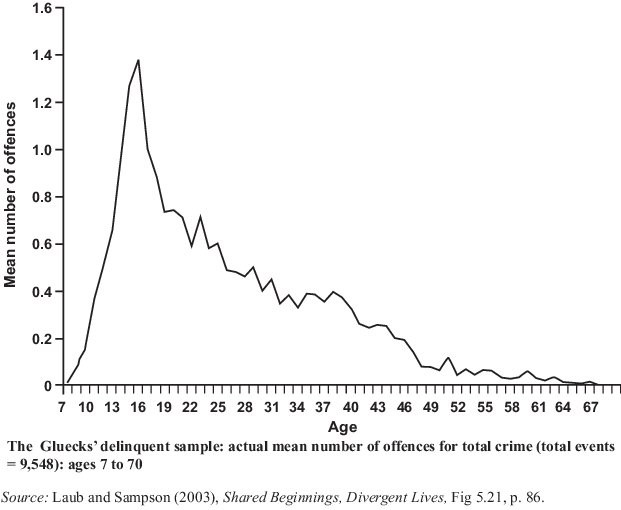

There is no single definition that can describe a criminal actor. Individual actors can differ in age, motivation, type of act and life course. Researchers did find consensus on risk factors that can influence the decision to commit a crime. Age, life events, social status and personality traits are significant predictors of crime. The Age-Crime Curve shows that most offenders are between 15 and 25 years old.[2][3]

Adolescence limited offender

Many criminological research on the life course of offenders, shows that there is a peak in age between 15 and 25. The interpretation of the age-crime curve varies among criminologists and researchers. Moffitt’s Dual Taxonomy of the Life Course Persister versus the Adolescence Limited Persister is the most used and supported theory on individual criminal careers. Taxonomy is the study of dividing individuals into similar groups. In her Dual Taxonomy theory, Moffitt distinguishes individuals who engage in antisocial an criminal behavior during their adolescence and individuals that pursue a criminal career throughout the rest of their life (the so called life course persisters).[4] While the teenage brain is developing, inhibitions, impulsive behavior and sensation seeking traits can still be turned around. Experiencing interventions (youth programs) or certain life events (falling in love, getting into college) can stop this group from developing a criminal career.

Life course persisters

Biological and psychological risk factors such as low intelligence, high impulsivity, low self control can be indicators of the development of a criminal way of life. The Life Course Persister is regarded as the individuals that have not experienced the previously mentioned Life Events or interventions or have not benefited from their desisting influence. Examples of Life Course Persisters are drug criminals, addicts that remain to steal to afford their drugs, or violent, homicidal or sexual offenders, that have not received therapy or interventions before their brains fully developed.

Life course persisters

The FBI conducted research on murderers in the 1970s in the United States. Around that time, lots of young people were hitchhiking and due to social trends (drugs, festivals), many young people travelled freely around the country. In that time, the amount of homicides also increased, because these trends made it a lot easier for killers to pick up their victims. The chances of getting caught were very low, because the young victims were relatively anonymous and often far away from home. The FBI came up with a term, describing killers that killed two or more victims; serial killers. Not to be confused with a mass or spree killer, which they distinguished in the same taxonomy. A serial killer has a cooling down period in between kills. For a serial killer, the act itself is almost a compulsion. He needs time to prepare to make it perfect and to maximize the sensation of killing. A spree killer also commits multiple homicides, but within a very short period (max. 30 days), with a different motive. A mass killer carries out one single acts, in which he or she tries to kill as much victims as possible, often out of anger or with a political motive, such as lone wolves or school shooters.

Lone wolves

Lone wolves do not operate within a group or in the role of a steady member of a large terrorist cell or of an organisation. The inspiration of a lone actor terrorist, also frequently described as ‘lone actor terrorists’, frequently comes from publications of like-minded individuals through online and offline contact. The explosive amount of violence, that is often used by lone actor terrorists, frequently overshadows their ideology and becomes the ideology itself. A significant difference between jihadist and right-wing lone actors lies in their psychopathology.

Groups

Our society as a whole, consists of different groups and subcultures. As a society, we have set certain goals to achieve, such as creating a meaningful career for yourself, starting a family and creating happiness for yourself. The means to achieve these goals are not the same for everyone unfortunately. Trying to achieve these goals, when one has the right means, such as a paying job, not having a criminal record et cetera, will be much easier than not possessing those means. When the culturally set goals are not reachable without certain means, strain comes to play. Strain, simply explained is the emerging of social deprivation that leads to groups that create their own subcultures within the existing culture. These subcultures create their own morals and values, so called anomie, for they cannot comply to the general laws[5].

Different groups experience different types of strain and will therefore also commit different types of criminal acts[6]. An important notion is that the longer a group feels separated and stigmatised from society as a whole, and is labelled deviant by that same society, the more invested they become in creating their own subcultures. They feel less and less attached, by certain sociological processes and values in society. Examples of these subcultures and groups are youth delinquent groups that have had bad attachment to family and school, neo-nazi groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, Roma’s, organised criminal groups such as maffia’s, criminal networks or terrorist organisations[7].

Organised

Until the 1990s, organised crime was known as crime carried out by groups with a pyramidal structure containing a strict hierarchy, such as maffia organisations in Italy or the United States of America. In 1983 RICO, the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organisations Act was introduced, cleaning out criminal “enterprises”. This led to a shift from pyramid structures within criminal organisations to ‘nodal networks’ and ‘cells’.

Nodal networks

In between the roaring twenties and 1990s most organised criminal networks were mostly formed from families with a hierarchical structure, after the 1990s social embeddedness became more important. Criminal networks dispersed and formed smaller groups that were connected by ‘facilitators’ and ‘nodes’. Facilitators provide services for several smaller groups, such as bookkeeping (laundering money). Nodes are connecting individuals that can bring together different groups, such as an individual with a large (criminal) social network that can introduce key players. Often these nodal networks are drug related crime and/or white collar crime. Investigating these smaller, nodal networks posed a challenge for law enforcement due to the fact that they are less visible than large enterprises or syndicates. Therefore, law enforcement agencies focus on identifying facilitators to roll up entire networks.

Cells

The term ‘cell’ comes from epidemiology, a discipline that forms many similarities to criminology. In history, when a pandemic emerged, the treatment of the pandemic often flowed over to the treatment of crime (during the plague, lepracy and smallpox)[8]. A criminal ‘cell’ can lead back to a common origin, like a disease or virus can be traced back through contacts with an original source[9].

A terrorist cell is often a small group, that is either self-financing and organised, without being directed by larger organisations, but following their ideologies. For cells, there is no need to maintain an infrastructure and operational costs remain relatively low. Mainly when their modus operandi remains simple, costs stay low, for instance in the example of a terrorist cell carrying out an attack with a rented van or with three attackers with knives and/or firearms[10].

Peer groups (impulse)

Groups are not always organised. Mainly within situations of collective violence, such as riots, group violence can erupt with or without a direct motive or cause. A group can either be formed as a reaction on a certain event or provocation (i.e. soccer match, bar fights) or without a clear cause. Researchers have found that non-reactive group violence is often conducted by young men, that are looking for reasons to commit violent acts, also known as the “Young Male Syndrome”. Young males in this case have the tendency to take risks and think of short term advantages, seeking sensation, acting on impulses, instead of thinking about the long term effects of their actions.

Here you can find the other security threats related pages:

- Security threats: acts

- Security threats: mitigations

Footnotes and references

- ↑ Durkheim, E. (1893). De la division du travail sovial. – s.l.;s.n.

- ↑ Dijk, van. J. et al. (2009). Actuele Criminologie. Den Haag: Sdu Uitgevers.

- ↑ Laub and Sampson (2003), Shared Beginnings, Divergent Lives, Fig 5.21, p. 86.

- ↑ Moffitt, T.E. (1993). “Adolescence-Limited and Life Course Persistent Antisocial Behaviour: A Developmental Taxonomy”, Psychological Review, pp. 100:674-701.

- ↑ Merton, R.K. (1938). Social Structure and Anomie. American Sociological Review, 3(5), pp. 672-682. Retrieved on 22 November 2020, https://doi.org/10.2307/2084686

- ↑ Hirschi, T., & Gottfredson, M. R. (1995). Control theory and the life-course perspective. Studies on Crime & Crime Prevention, 4(2), 131–142.

- ↑ Dijk, van. J. et al. (2009). Actuele Criminologie. Den Haag: Sdu Uitgevers.

- ↑ Schuilenburg, Marc. (2015). The Securitization of Society. Crime, Risk, and Social Order (Introduction by David Garland)

- ↑ Finnegan J.C., Masys A.J. (2020) An Epidemiological Framework for Investigating Organized Crime and Terrorist Networks. In: Fox B., Reid J., Masys A. (eds) Science Informed Policing. Advanced Sciences and Technologies for Security Applications. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41287-6_2

- ↑ Europol (2020). European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report. https://www.europol.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/european_union_terrorism_situation_and_trend_report_te-sat_2020_0.pdf. Accessed 10 11 2020.